Meetings with my librarian colleagues are usually quite amicable. Except when it comes to what makes something a primary source. Then the clashes start. I'm not kidding. There have literally been arguments where voices are raised as we've wrestled with this question as a group. I thought about those lively discussions when I recently realized that my own definition for what makes something a primary source had changed.

For the last couple of years, I had used two resources to shape my definition of a primary source. The first is from the Library of Congress. One description it gives is that primary sources are "original documents and objects created at the time under study." It also goes on to read that "They are different from secondary sources, accounts or interpretations of events created by someone without firsthand experience." The second source contradicts that somewhat. In a podcast episode from Creative Learning Factory, they focus on newspapers being a primary source. With many articles not being written by someone with firsthand experience, can we consider these primary sources? The podcast takes the position that "primary sources are either an eyewitness account or an artifact of its time." To me, if I wanted to know what a greater community would know of an event, a newspaper article would qualify as a primary source of that question.

Earlier this year, the students did an activity where they analyzed primary sources of scientists notes and writings to investigate how they organize their work and their thinking. The sources were from all different time periods and a variety of scientists. Students recognized organizational strategies of these scientists and connected them to their own writing as elementary student scientists.

During other activities where I had utilized primary sources with students, there was a focus around a date, year, or range of time. We used primary sources to focus on colonial times, the building of a American symbol, or the time when a famous individual was alive. There was a beginning date and ending date. Even when we would focus on events like Thanksgiving or Halloween, the date would be important. What was Thanksgiving like 70 years ago? How did they celebrate Halloween 100 years ago? I could even attach specific dates to these types of investigations, and more importantly, many times the dates were important for us to compare our lives with those of others or to put it into a chronological context for our understanding.

With our activity about scientists and their notes, that specific date didn't seem to matter. Instead, the moment in time mattered, that moment when the scientist was writing down his or her ideas, questions, or observations. While we had information on when those moments took place, they weren't important to the analysis of the primary source or the understanding that they were working to come to. Students didn't need the date that Alexander Graham Bell wrote about his experiment to come to understand how he decided to record his ideas and they didn't need to know the year that Leonardo da Vinci drew illustrations of a bow to compare his method to theirs.

Is this new viewpoint unique to using primary sources in certain science settings? I don't think so, but it was what moved my thinking forward. I think the same idea of a primary source not being attached to a date, but a moment in time would apply in the work our fifth graders have done when using primary sources to define geocentric and heliocentric models of the solar system. What made those resources primary sources in that case wasn't the year they were created (although you could have done another activity with that being an important factor) but that these images were products of moments when these scientists were creating or defining either a geocentric or heliocentric model of the solar system.

I realize that this original misconception was not caused by a faulty definition by the Library of Congress or a misspoken idea in a podcast. It was my interpretation of those things that was flawed. To me, that word "time" in the definitions originally meant that date or date range or era. What I failed to think about was about "time" as "moments" Those moments could be scattered over years, decades, or centuries. And artifacts could have been created in all of those moments that are connected, not by the date, but by the activity or intention by the creator of the artifact at that moment.

I'm sure that my working definition of a primary source will continue to evolve over time. For now, I am looking forward to that next spirited discussion with my fellow librarians.

Friday, December 12, 2014

Friday, December 5, 2014

Reaction to John Stephens' The Black Reckoning (book 3 in The Books of Beginnings series)

I just finished reading an advanced copy of John Stephens' The Black Reckoning. I can't say I ran across it. It was more like I hunted it down. I'll admit that I'm a big fan of the first two books in the Book of Beginnings series, The Emerald Atlas and The Fire Chronicle, so when me asking a local bookseller about the final book in the series and the ARC showing up at her desk coincided, I knew I had to hunt it down.

Now I usually don't read second or third books in a series. As an elementary librarian, I think I need to be widely read, so I usually just read the first book so I can recommend it with some authority and then move on to the next series. After I picked up The Black Reckoning though, I had to reread the first two books in the series, not because I forgot what had happened, but just because I enjoyed the first two books so much. Neither of them disappointed the second time and either did The Black Reckoning.

The Black Reckoning picks up right where The Fire Chronicle leaves off. Emma, the youngest of the siblings, has been kidnapped, leaving Kate and Michael, along with a great supporting cast, to find her. They do find Emma, and sooner than I thought. I was glad too because it is when the three siblings are together that the story is at its best. Their unique voices can be heard and there is evidence of growth as they really begin to change, both as characters and in how they view each other, that is refreshing to see over the series of books.

Of course, there are other relationships there too. The most focused in this story is Kate's relationship with Rafe (spoiler alert!) who turns into the Dire Magnus at the end of the second book. How can this happen when it is 100 years after Kate left Rafe? You'll find out. And Michael's relationship with the elf princess? It is just as funny but a bit endearing too as Michael allows himself to be more than just embarrassed by her attention.

The fantasy element is in full force as well. The story continues with trolls, elves, and other characters from the first two books. The author also brings in giants (and their gross but funny hygiene issues) and carriadin, found in the land of the dead. Other characters pop up again as well. While I won't give away the details, the arrival and departure of the witch from The Emerald Atlas was one of my favorite parts of the book.

If you've read the first two books, you'll know that the final book in the series deals with Emma finding her magical book, referred to both as The Book of Death and The Black Reckoning. (While I'm not positive why Stephens gives the book two names, I'm guessing it has something to do with the book in the story being the title of the story itself. Watching your child read The Black Reckoning is probably more palatable than them flipping through the pages of The Book of Death.) Stephens does a good job of limiting the strengths the children have gathered along the way like the power of the two other books or their large cast of supporting characters from Dr. Pym to Gabriel.

And then there are the concerns from adults about these books. I hear that they are too predictable or borrow too much. And I wouldn't disagree with the basics of that concern. There are hints of other stories in here and you know from the beginning of the first book how this final book will end, with the three children defeating evil, the Dire Magnus. But what makes these books ones that I want to reread or hunt down the newest copy of is not the end of the story, it is the journey that John Stephens brings us on. It is the relationship of Kate, Michael, and Emma. It is great moments of dialogue, especially from Emma. It is the twists and turns and reading how these characters deal with them that makes this ride an enjoyable ending to a great series.

The Black Reckoning is scheduled to be released on April 7, 2015.

Now I usually don't read second or third books in a series. As an elementary librarian, I think I need to be widely read, so I usually just read the first book so I can recommend it with some authority and then move on to the next series. After I picked up The Black Reckoning though, I had to reread the first two books in the series, not because I forgot what had happened, but just because I enjoyed the first two books so much. Neither of them disappointed the second time and either did The Black Reckoning.

The Black Reckoning picks up right where The Fire Chronicle leaves off. Emma, the youngest of the siblings, has been kidnapped, leaving Kate and Michael, along with a great supporting cast, to find her. They do find Emma, and sooner than I thought. I was glad too because it is when the three siblings are together that the story is at its best. Their unique voices can be heard and there is evidence of growth as they really begin to change, both as characters and in how they view each other, that is refreshing to see over the series of books.

Of course, there are other relationships there too. The most focused in this story is Kate's relationship with Rafe (spoiler alert!) who turns into the Dire Magnus at the end of the second book. How can this happen when it is 100 years after Kate left Rafe? You'll find out. And Michael's relationship with the elf princess? It is just as funny but a bit endearing too as Michael allows himself to be more than just embarrassed by her attention.

The fantasy element is in full force as well. The story continues with trolls, elves, and other characters from the first two books. The author also brings in giants (and their gross but funny hygiene issues) and carriadin, found in the land of the dead. Other characters pop up again as well. While I won't give away the details, the arrival and departure of the witch from The Emerald Atlas was one of my favorite parts of the book.

If you've read the first two books, you'll know that the final book in the series deals with Emma finding her magical book, referred to both as The Book of Death and The Black Reckoning. (While I'm not positive why Stephens gives the book two names, I'm guessing it has something to do with the book in the story being the title of the story itself. Watching your child read The Black Reckoning is probably more palatable than them flipping through the pages of The Book of Death.) Stephens does a good job of limiting the strengths the children have gathered along the way like the power of the two other books or their large cast of supporting characters from Dr. Pym to Gabriel.

And then there are the concerns from adults about these books. I hear that they are too predictable or borrow too much. And I wouldn't disagree with the basics of that concern. There are hints of other stories in here and you know from the beginning of the first book how this final book will end, with the three children defeating evil, the Dire Magnus. But what makes these books ones that I want to reread or hunt down the newest copy of is not the end of the story, it is the journey that John Stephens brings us on. It is the relationship of Kate, Michael, and Emma. It is great moments of dialogue, especially from Emma. It is the twists and turns and reading how these characters deal with them that makes this ride an enjoyable ending to a great series.

The Black Reckoning is scheduled to be released on April 7, 2015.

Monday, December 1, 2014

Taking Notes Like a Scientist: Using Primary Sources to Examine Note Taking Strategies

Last summer, I participated in the Library of Congress Science Seminar, a five day professional development opportunity that allowed me to begin exploring the integration of primary sources as a resource in science instruction. As part of that week, I made a plan on one way to integrate primary sources with the direction to implement the lesson during the first half of the school year.

My idea for a lesson revolved around science note booking and note taking in our school. In 3rd grade, our science teacher introduces the process. It continues through their elementary career. During a book study last year on research, using Chris Lehman’s book “Energize Research Reading and Writing”, I saw many correlations between the free form style that students use when science note booking and the introduction to note taking styles with student choice based on need emphasized in Lehman’s book.

I saw them as two styles that could complement the other. My question was how to bridge the gap between the two. While at the Seminar, I decided primary sources might be the answer. Through the use of primary sources, students could connect their own natural tendencies to organize information through science note booking with tried methods to organize information that scientists have used in the past. Instead of teachers demonstrating note taking methods, students would discover the note taking methods of actual scientists and attempt to incorporate those methods into their own note taking. These methods could transfer into note taking in other subject areas as needs arose.

During the first week of school, third grade students participated in the note booking emersion. They observed fish, plants (and all of the insects on them), and other scientific phenomena. During their excursion, many students saw some type of small eggs on melon leafs in the school garden. This caused a lot of excitement and speculation. The classroom teacher had a naturally generated question and we decided to run with it. Students would do a mini research project trying to answer their question and I would help them think about their note taking in the process.

During the first week of school, third grade students participated in the note booking emersion. They observed fish, plants (and all of the insects on them), and other scientific phenomena. During their excursion, many students saw some type of small eggs on melon leafs in the school garden. This caused a lot of excitement and speculation. The classroom teacher had a naturally generated question and we decided to run with it. Students would do a mini research project trying to answer their question and I would help them think about their note taking in the process. |

| http://www.loc.gov/item/magbell.25300102/ |

Students began their study of scientists’ notes by analyzing a page from a notebook of Alexander Graham Bell. Students used a modified version of the Primary Sources Analysis Tool from Library of Congress. For the purposes of this lesson and because of time restrictions, I wanted students to focus in on what they saw as an organizational tool (Observation) and why they thought the scientist organized his information in this way (Reflection).

Students found a great deal of organizing methods. Pages were numbered, ideas were dated and sorted into short paragraphs. There were drawings of Bell’s telephone that was labeled with letters and those corresponding letters were used in his writing about the device. And in each method, students were able to give some reflection as to the “why” of its use. “Short paragraphs are easier to read.” “If you date things, you’ll know what order you did them in.” “Labeling the picture and using the labels in his writing helps me understand what he is writing about.”

Smaller groups then continued by analyzing another note or recording method of a scientist. Students analyzed the directions for using a macaroni machine written by Thomas Jefferson. They explored the drawings for a crossbow by Leonardo da Vinci. Students even looked at more recent notes by Dave Morrison as he thought about measuring the surface temperature on Mars.

Smaller groups then continued by analyzing another note or recording method of a scientist. Students analyzed the directions for using a macaroni machine written by Thomas Jefferson. They explored the drawings for a crossbow by Leonardo da Vinci. Students even looked at more recent notes by Dave Morrison as he thought about measuring the surface temperature on Mars.

In these other works, students noticed drawings done from different perspectives, underlined and circled words, tables, step by step directions, and different ideas for the same goal drawn side by side. In each case, students were, again, able to express an idea about why the scientist chose to organize his thinking in that way. “It makes it easier to read.” “This was probably really important.” “You can see different details when he draws it this way.”

We extended the activity by asking students to look at their initial writing and drawing from their note booking experience. Could they see similarities between their work and the work of the scientists? They shared example after example, further reinforcing themselves as scientists and their work as scientific. I also feel they saw the work they do in a school setting existing outside of and beyond school. This skill was important and was used by great minds! Finally, I asked them, “As you take more notes, either from observations or from reading or viewing images, what strategies did these scientists use to organize their information that could help you?” Many shared ideas directly from their findings through the primary source analysis.

As they moved forward with their study, I did revisit their second set of notes and there were definite similarities between their work at the scientists’ work they studied. My hope is that this has laid a foundation and gives examples to call back to as students continue to explore note taking.

As they moved forward with their study, I did revisit their second set of notes and there were definite similarities between their work at the scientists’ work they studied. My hope is that this has laid a foundation and gives examples to call back to as students continue to explore note taking.

note: For anyone trying something similar, I will share that I did have to make transcripts of much of the notes because of the cursive handwriting. While students were willing to make attempts, the struggle would have slowed down the activity too much.

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

My Favorite Thanksgiving Primary Sources

This week really starts the Thanksgiving season for me. The five class days before the Thanksgiving break, the students and I do different kinds of Thanksgiving activities. Really, we analyze and investigate all kinds of Thanksgiving primary sources, kindergarten through fifth grade.

I know this might not sound like fun, not compared to crafty activities or reading a great Thanksgiving picture book. I would argue that it is better though. I see it as a discovering of knowledge about Thanksgivings past. In each grade, we focus on a different primary source or set of primary sources, and we don't just analyze them. We try to go further. This is something that I try to emphasize with my students. What do you do with that knowledge about the primary source you just analyzed? What can you connect it to? How can it help you look at something else in a different way? How can you use it to compare life now to life at another time? For this set of activities, we typically talk through this. In other activities, we may write or illustrate. With the excitement that leads up to Thanksgiving break, the students often want to talk, so I take advantage of that.

I thought I would share my favorite Thanksgiving primary sources.

Kindergarten students will be analyzing a wonderful photo from 1911 of students in a schoolyard titled

School Children's Thanksgiving Games. In the photo, some students sit on a bench watching other students who are in different Thanksgiving costumes. My favorite find in the photo, a child wearing a turkey mask, hasn't been seen by a student yet. See if you can find it.

After analyzing this photo, students compare these students celebrating Thanksgiving to their school celebrations at RM Captain.

In first and second grade we move the celebration from school to home and analyze photos from the Crouch family's Thanksgiving taken in 1940. These twenty photos are a wonderful snapshot of a Thanksgiving day in a large family's home. While the photos don't individually contain the detail that

the 1911 school photo does, as a group, they are rich with information about culture and tradition.

In first grade we will focus in on a photo of Mrs. Crouch pouring water on the turkey, the photo of the pies with the family visible in the mirror's reflection, and the photo of the whole family eating with the children at a separate table. Students will fully analyze one of the photos with the Observe, Reflect, Analyze model (using I see, I think, and I wonder) and do a lighter, quicker analysis of the others where we focus in on only what we see. Similar to kindergarten's comparison to school, first grade students compare their home celebrations to the Thanksgiving celebration in the photos.

In second grade, students will analyze several photos in groups, focusing their analysis on where events are taking place in the photos. In groups, they will attempt to create a map of the Couch's kitchen where the meal was cooked and eaten, highlighting furniture and other points of interest from the photos in their map.

Third grade students are going to be building on the first grade idea of the Thanksgiving meal

traditions and be planning their own Thanksgiving meal with a primary source twist. The class will collaborate on items for the meal and then shop in two places. Two groups will use a current local grocery store advertisement. Two other groups will use newspaper advertisements from about 90 years ago. The two advertisements, the first from 1919 and the second from 1922, list many items that students may use today. I'm eager to see if it does the job. While we won't be doing a traditional analysis on these pieces, I'm looking forward to the math and problem solving connections.

Fourth grade students will work with my favorite Thanksgiving primary sources. Earlier this year, our fifth grade classes did a primary source analysis to learn about a lost Halloween tradition. Our fourth graders will learn about a lost Thanksgiving tradition. They will first analyze a hundred year old photo of Thanksgiving Maskers, a group of boys dressed in costume who look like they are more fit for Halloween night. Following their analysis, which may leave more questions than answers, they will read a newspaper editorial from the same time period where the writer shares her distain for the maskers tradition of walking down the sidewalk banging pots and blowing horns, and asking passersby for pennies or candy while families are trying to enjoy their Thanksgiving. Learning about this lost tradition gives students a chance to be historians and investigate the a tradition completely foreign to them.

Finally, in fifth grade, students will be looking at Thanksgiving officially being named a national

holiday with Lincoln's 1863 proclamation while analyzing an 1861 drawing of Civil War soldiers celebrating Thanksgiving in camp. Hoping that students see that Thanksgiving was being celebrated before being named an official holiday, they will then use a secondary source to give them an overview of other presidents making Thanksgiving proclamations going back to George Washington.

I'm looking forward to this week with students before Thanksgiving, not just because of the great primary sources that they will be interacting with. I'm also looking forward to the K-5 experience throughout the entire building all connecting back to different learning around Thanksgiving as well as the potential experiences that students have year after year with these primary sources.

I know this might not sound like fun, not compared to crafty activities or reading a great Thanksgiving picture book. I would argue that it is better though. I see it as a discovering of knowledge about Thanksgivings past. In each grade, we focus on a different primary source or set of primary sources, and we don't just analyze them. We try to go further. This is something that I try to emphasize with my students. What do you do with that knowledge about the primary source you just analyzed? What can you connect it to? How can it help you look at something else in a different way? How can you use it to compare life now to life at another time? For this set of activities, we typically talk through this. In other activities, we may write or illustrate. With the excitement that leads up to Thanksgiving break, the students often want to talk, so I take advantage of that.

I thought I would share my favorite Thanksgiving primary sources.

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004010001/ |

School Children's Thanksgiving Games. In the photo, some students sit on a bench watching other students who are in different Thanksgiving costumes. My favorite find in the photo, a child wearing a turkey mask, hasn't been seen by a student yet. See if you can find it.

After analyzing this photo, students compare these students celebrating Thanksgiving to their school celebrations at RM Captain.

In first and second grade we move the celebration from school to home and analyze photos from the Crouch family's Thanksgiving taken in 1940. These twenty photos are a wonderful snapshot of a Thanksgiving day in a large family's home. While the photos don't individually contain the detail that

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa2000023954/PP/ |

In first grade we will focus in on a photo of Mrs. Crouch pouring water on the turkey, the photo of the pies with the family visible in the mirror's reflection, and the photo of the whole family eating with the children at a separate table. Students will fully analyze one of the photos with the Observe, Reflect, Analyze model (using I see, I think, and I wonder) and do a lighter, quicker analysis of the others where we focus in on only what we see. Similar to kindergarten's comparison to school, first grade students compare their home celebrations to the Thanksgiving celebration in the photos.

In second grade, students will analyze several photos in groups, focusing their analysis on where events are taking place in the photos. In groups, they will attempt to create a map of the Couch's kitchen where the meal was cooked and eaten, highlighting furniture and other points of interest from the photos in their map.

|

| http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89081022/1922-11-22/ed-1/seq-5/ |

Third grade students are going to be building on the first grade idea of the Thanksgiving meal

traditions and be planning their own Thanksgiving meal with a primary source twist. The class will collaborate on items for the meal and then shop in two places. Two groups will use a current local grocery store advertisement. Two other groups will use newspaper advertisements from about 90 years ago. The two advertisements, the first from 1919 and the second from 1922, list many items that students may use today. I'm eager to see if it does the job. While we won't be doing a traditional analysis on these pieces, I'm looking forward to the math and problem solving connections.

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/ggb2004010002/ |

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004660226/ |

holiday with Lincoln's 1863 proclamation while analyzing an 1861 drawing of Civil War soldiers celebrating Thanksgiving in camp. Hoping that students see that Thanksgiving was being celebrated before being named an official holiday, they will then use a secondary source to give them an overview of other presidents making Thanksgiving proclamations going back to George Washington.

I'm looking forward to this week with students before Thanksgiving, not just because of the great primary sources that they will be interacting with. I'm also looking forward to the K-5 experience throughout the entire building all connecting back to different learning around Thanksgiving as well as the potential experiences that students have year after year with these primary sources.

Friday, October 31, 2014

When Primary Sources do Double Duty OR When Halloween and Politics Collide

Earlier this week, I posted about a primary source analysis that a class of fifth graders did. The focus was on lost traditions, specifically, the lost superstitions of doing certain activities to find your spouse on Halloween. We used an 1896 drawing along with a newspaper article to uncover the lost superstition of looking at a mirror holding a candle to look for the image of your future spouse. Through my own analysis and with the help of some others, I found out quite a bit more about the drawing and the intention behind it.

Through the analysis of the 1896 drawing, many students focused on the dress of the woman shown. Her top is covered with stars, the bottom with stripes, giving it a flag effect that is difficult to ignore. She stands at a dresser and mirror, her hand on a candle. There is a reflection of a man in the mirror. The man shown in the reflection isn't the dashing young man that one might expect to be shown in the representation of this superstition. Four days ago, when I found the newspaper article that referenced the superstition, I was just happy that I had some understanding of the image.

Then, another layer of the drawing started to reveal itself. First, an educator in the TPS Teachers Network that I am a part of shared a similar image. This one referenced the tradition in a satire of the 1904 election. In the image, Uncle Sam is walking down the stairs holding a candle and a mirror. In the mirror is the image of Teddy Roosevelt. In the background, other candidates walking around with candles and mirrors looking for their "match". I wondered about the woman in stars and stripes from the other picture, but hadn't put together the pieces yet.

That afternoon, another fifth grade class came in for the activity. The teacher was very active and

jumped right in to do the analysis of the drawing with the students. As students read the newspaper article, I asked if she had ever heard of this superstition. She shared that she hadn't, but it made her wonder more about the questions that she had written as part of her analysis and wondered aloud if there was an election in 1896. Everything clicked into place for me. I shared a little about the other picture and she quickly looked up information on the 1896 election. There, on wikipedia, was an image of William McKinley which bore a eerie resemblance to the "ghostly" image in the mirror from the 1896 drawing. We were left with a new interpretation, that of Lady Liberty looking for her future spouse.

There I discovered a whole new meaning to this 1896 drawing. It was the political satire of the day. The 8th grade social studies teacher could use this in studies of the late 1800's. The high school political studies teacher could pair these images with more current political cartoons involving Halloween traditions. Either class could explore the illustrator's intended audience. Those aren't areas that I would explore with fifth grade students, but them learning the tradition could give them key background knowledge if revisiting the primary source later.

In addition to the many places this primary source could work among different grade levels, the collaboration to get to meaning is worth noting. I made my own learning discoveries with the help of colleagues. Without them, I would never have discovered that deeper meaning to the 1896 drawing. Similarly, students benefit when discussing primary sources together. Their thinking is stretched and challenged. Pieces of understanding from multiple students can be put together to deeper meaning than they can achieve alone. While it may not be appropriate to constantly have students collaborating during the analysis of a primary source, having them come together at different points in the process can reap great benefits.

Through the analysis of the 1896 drawing, many students focused on the dress of the woman shown. Her top is covered with stars, the bottom with stripes, giving it a flag effect that is difficult to ignore. She stands at a dresser and mirror, her hand on a candle. There is a reflection of a man in the mirror. The man shown in the reflection isn't the dashing young man that one might expect to be shown in the representation of this superstition. Four days ago, when I found the newspaper article that referenced the superstition, I was just happy that I had some understanding of the image.

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2011645580/ |

That afternoon, another fifth grade class came in for the activity. The teacher was very active and

|

| http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_presidential_election,_1896 |

There I discovered a whole new meaning to this 1896 drawing. It was the political satire of the day. The 8th grade social studies teacher could use this in studies of the late 1800's. The high school political studies teacher could pair these images with more current political cartoons involving Halloween traditions. Either class could explore the illustrator's intended audience. Those aren't areas that I would explore with fifth grade students, but them learning the tradition could give them key background knowledge if revisiting the primary source later.

In addition to the many places this primary source could work among different grade levels, the collaboration to get to meaning is worth noting. I made my own learning discoveries with the help of colleagues. Without them, I would never have discovered that deeper meaning to the 1896 drawing. Similarly, students benefit when discussing primary sources together. Their thinking is stretched and challenged. Pieces of understanding from multiple students can be put together to deeper meaning than they can achieve alone. While it may not be appropriate to constantly have students collaborating during the analysis of a primary source, having them come together at different points in the process can reap great benefits.

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

When that 92 Year Old Halloween Newspaper Article ISN'T a Primary Source

What makes something a primary source? Before I attended the Library of Congress Summer Institute, I thought I knew, but a definition by the Library of Congress, has helped me evolve that definition.

The Library of Congress gives three descriptors when defining a primary source. They describe primary sources as the "raw materials of history." To further define this, they also describe them as "original documents and objects which were created at the time under study" and differentiate them from secondary sources which were "created by someone without firsthand experience." I revisited this definition recently when preparing a Halloween activity for fifth grade students.

Students like looking back in time. What was Halloween like 50 years ago? 100 years ago? Primary sources can provide answers to those questions. For this activity, I focused on a 1896 drawing of a woman, her hand resting on candle and looking into a mirror with a reflection of a man. I had looked at the image many times and it made little sense to me. I thought it might be a reference to a ghost or deceased loved one, but her lack of expression confused me.

Recently, I explored Chronicling America for newspaper articles on Halloween. I found a 1922 article titled Mischief Night which may explain the photo. The article references a superstition that on Halloween a woman could hold a candle to a mirror and see her future husband's face. The article implies that she must be walking down the stairs backwards when doing this, but the general idea is portrayed in the drawing. I felt it helped to shed light on the drawing and it was short enough that I could use it as part of a lesson on this lost superstition.

As I prepared to use the article, I asked the question, was this a primary source? If I was asking myself what Halloween was like 120 years ago, this newspaper writing didn't qualify. It was written 92 years ago, a generation after the drawing was created. In addition, the article read, "Time was, when Hallowe'en..." when describing the superstition with the mirror, referencing something that existed in the past. In this context, this article was a secondary source.

Did I still use the article? Absolutely. Students analyzed the drawing and, in small groups, came to consensus on what the illustrator was trying to portray. They then read the article and had an opportunity to revise their thinking. The lesson went wonderfully and as part of that lesson, the students and I had a great discussion about what makes something a primary source. Finally, I asked the students what I could do if I wanted to confirm this account from 25 years after the drawing. A couple of students suggested that finding a newspaper from 1896 that referenced Halloween could be a solution. From there I was able to briefly share two primary source articles, one from 1891 and another from 1895, that referenced Halloween as a night to "reveal your future spouse's face" and when "maidens try to find out who will wed them."

Something being "old" doesn't make it a primary source. Instead, looking at the time period you are studying will help to define if that image, map, document, or object is a primary or secondary source and while that doesn't determine whether you will use it or not with your students, it can impact how you approach using the resource.

The Library of Congress gives three descriptors when defining a primary source. They describe primary sources as the "raw materials of history." To further define this, they also describe them as "original documents and objects which were created at the time under study" and differentiate them from secondary sources which were "created by someone without firsthand experience." I revisited this definition recently when preparing a Halloween activity for fifth grade students.

|

| http://cdn.loc.gov/service/pnp/acd/2a07000/2a07300/2a07327r.jpg |

Recently, I explored Chronicling America for newspaper articles on Halloween. I found a 1922 article titled Mischief Night which may explain the photo. The article references a superstition that on Halloween a woman could hold a candle to a mirror and see her future husband's face. The article implies that she must be walking down the stairs backwards when doing this, but the general idea is portrayed in the drawing. I felt it helped to shed light on the drawing and it was short enough that I could use it as part of a lesson on this lost superstition.

As I prepared to use the article, I asked the question, was this a primary source? If I was asking myself what Halloween was like 120 years ago, this newspaper writing didn't qualify. It was written 92 years ago, a generation after the drawing was created. In addition, the article read, "Time was, when Hallowe'en..." when describing the superstition with the mirror, referencing something that existed in the past. In this context, this article was a secondary source.

Did I still use the article? Absolutely. Students analyzed the drawing and, in small groups, came to consensus on what the illustrator was trying to portray. They then read the article and had an opportunity to revise their thinking. The lesson went wonderfully and as part of that lesson, the students and I had a great discussion about what makes something a primary source. Finally, I asked the students what I could do if I wanted to confirm this account from 25 years after the drawing. A couple of students suggested that finding a newspaper from 1896 that referenced Halloween could be a solution. From there I was able to briefly share two primary source articles, one from 1891 and another from 1895, that referenced Halloween as a night to "reveal your future spouse's face" and when "maidens try to find out who will wed them."

Something being "old" doesn't make it a primary source. Instead, looking at the time period you are studying will help to define if that image, map, document, or object is a primary or secondary source and while that doesn't determine whether you will use it or not with your students, it can impact how you approach using the resource.

Tuesday, October 21, 2014

Adapting Text-Based Primary Sources for Elementary Students

I was excited to see that the fifth grade teachers at RM Captain are integrating primary sources into some of their history teaching. Some challenges they were facing in using text-based primary sources and how they are addressing those challenges is worth sharing. Text-based primary sources can include letters, journals, diaries, laws and government records, newspapers, speeches, transcripts of interviews, or any primary source where text is the main component.

In a recent collaboration with the fifth grade teachers, they were excited to share an activity that relied on primary sources on the topic of the Jamestown colony for students to make decisions about founding their own colony and, in the process, come to some understanding of why cities and towns were initially located in certain places.

The teachers shared their resources with me. They had a number of text-based primary sources. I was interested to see how the students interacted with them, so I asked Mrs. Ketzer, one of the teachers, how the project was going.

Mrs. Ketzer shared that she didn’t think the students were connecting with the primary sources and that they were struggling with them. She shared that they were using the same process of making observations, reflections, and questions that we had done in the library with other primary sources.

We spoke about the primary sources that they used. Some of them were longer texts. Even shorter texts had difficult vocabulary. All of the primary sources were transcribed, but were copies of copies with black print on grey background. Through our discussion, we came up with several ideas to present the primary sources in a way that may help the students connect with them more effectively.

We spoke about the primary sources that they used. Some of them were longer texts. Even shorter texts had difficult vocabulary. All of the primary sources were transcribed, but were copies of copies with black print on grey background. Through our discussion, we came up with several ideas to present the primary sources in a way that may help the students connect with them more effectively.- Retype the text so that it looked more clean and was a little larger. It would be easier to read. Removing distractions allows students to focus.

- For longer passages, choose chunks that are important for students to analyze. While older students may be able to read and analyze a large passage, younger students can be more successful with shorter passages. Choose the piece(s) you hope they would focus in on. Isolate them and let students interact with them.

- Provide a glossary on the same page, allowing students to understand the text without leaving it. Text written even a few decades ago may have words or phrases that students have never seen. Reading around the text in a small passage may make it difficult or impossible for them to come to an understanding of the text or it may be confusing.

- Provide space for students to make reflections and questions on the same page. (With text based primary sources, we typically make observations right on the copy of the primary source.) Having the source and analysis in the same place allows easy access when using their thoughts for the next steps of learning.

I checked in with her and Mrs. Crowley, the other 5th grade teacher doing the simulation with her students, a few days later to see how the updated presentation of the primary sources were going. They both felt students were much more engaged with the text. One student, who was close by and listening to our conversation added, “It’s so much easier to read.”

As we present primary sources to students, it is not only important to choose the best primary source for students to analyze, but also to present the primary source in a way that encourages a student to engage and interact with it.

As I was writing this blog post, I found this article on making text-based primary sources more accessible for students. You may find it an interesting addition.

As I was writing this blog post, I found this article on making text-based primary sources more accessible for students. You may find it an interesting addition.

Sunday, October 5, 2014

Taking Chistopher Columbus' Journal One Step Further

Years ago, when I was still in the classroom, we used translations of Christopher Columbus' journal in class. I read it to students or they read it on their own. They took on the role of a shipmate and wrote their own journal entry. It all felt "okay" but was missing something. I think a recent activity with two fifth grade classrooms got closer to meaningful learning.

During collaboration, two of our fifth grade teachers were studying the time period encompassing European exploration. They wanted to push their own teaching forward and had collected many resources on the typical explorers that students study. Since I have been doing several activities with primary sources, they asked if I would do an analysis of Columbus' journal entries with the students. They handed me a packet of journal entries. I agreed that we could do something with the entries.

I knew we were under time limitations, less than two hours. They were coming to the library during one of their social studies periods. If I needed more time, I could take their weekly library visit as well. That time limitation always shapes our encounters with primary sources. Here, I knew I had to put specific journal entries in front of them. I chose three that I thought revealed Columbus' intentions better than the others. In one entry from October 12, 1492, he writes about meeting natives and taking possession of the island. In another from that same day, he writes about his desire to convert the natives to his religion. In the final shared entry from October 13, 1492, Columbus writes about his search for gold.

I had three entries that highlighted intentions that would impact Columbus' and other European explorer's encounters with Americans, but I was left with a feeling of "so what?" Students could analyze these writings and come to some understandings about Columbus and possibly those that he encountered, but what would allow them to solidify their thinking in action? This is another understanding that I've come to when using primary sources with students. While analyzing using the LOC Primary Source Analysis Tool is a powerful activity, there is a piece at the bottom that reads "Further Investigation". It challenges us to take that next step with students and not to let the analysis be the end of the learning.

I had three entries that highlighted intentions that would impact Columbus' and other European explorer's encounters with Americans, but I was left with a feeling of "so what?" Students could analyze these writings and come to some understandings about Columbus and possibly those that he encountered, but what would allow them to solidify their thinking in action? This is another understanding that I've come to when using primary sources with students. While analyzing using the LOC Primary Source Analysis Tool is a powerful activity, there is a piece at the bottom that reads "Further Investigation". It challenges us to take that next step with students and not to let the analysis be the end of the learning.

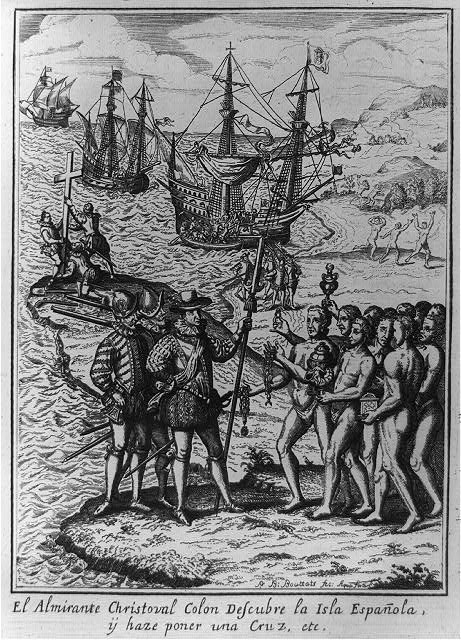

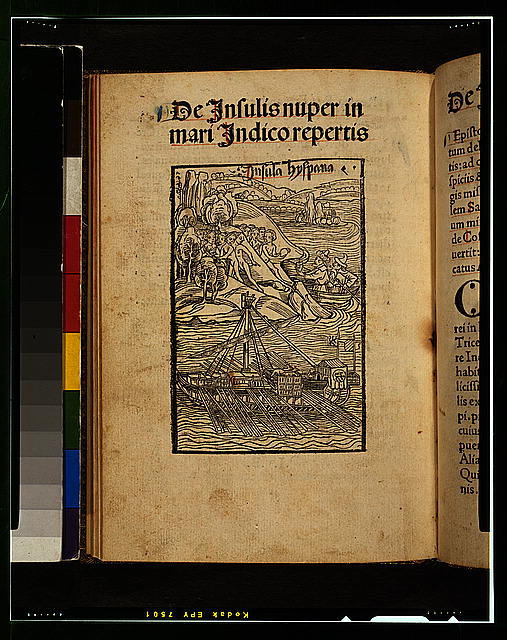

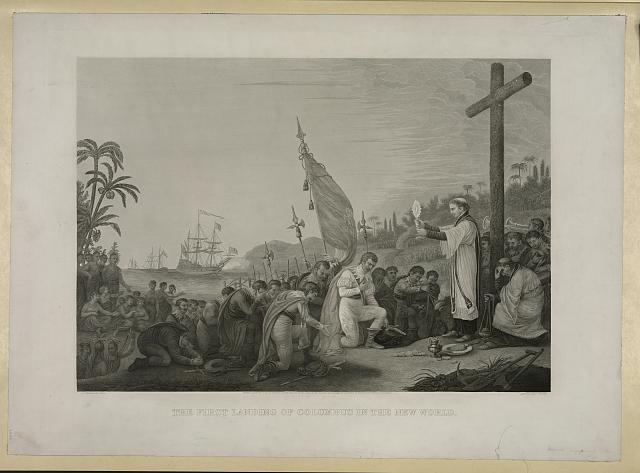

Again, I turned to primary sources. I thought about a piece of artwork depicting Columbus' landing that was used in a summer institute at the LOC that I attended in 2013. It was created in 1893, hundreds of years after Columbus' landing. We originally used it in a discussion where we began to form our definition of a primary source.

The interesting thing about the piece is that it seems to be influenced by the time period of when it was created and its creator. (I encourage you to read Rebecca Newland's ideas on sourcing and contextualizing.) Critiquing a interpretation of Columbus' landing based on his own words would provide an opportunity for students to show an understanding of the journal entries and apply that understanding to their critique.

I chose three different artist renditions of Columbus' landing. I felt they had three distinct perspectives and would allow the students to focus on different perspectives of the journal entries. My resources were ready.

Students, overall, did an incredible job on the analysis of the primary sources. I like to keep my directions simple, telling students to identify anything they think is important, interesting, or unusual. There is also a warning of not thinking everything is important, interesting, and unusual. Many reflections and questions spoke to the perspective of the natives, letting me know that they were identifying Columbus' perspective, but not solely identifying with that perspective. With some delays, we completed analyses of two of the journal entries in our first sitting. As students left, one said, "Thanks, that was fun," while I overheard another telling a fellow classmate, "I did the third analysis already even though we weren't supposed to." These were two small signs that we were on the right track.

During the students' next visit, we jumped back into the activity with them analyzing the third journal entry. After they finished this, I paired them up and gave them their final challenge. I told them I had three depictions of Columbus' first landing in the new world. They were all made after this journey and I wanted them to choose one that, based on what they knew, Columbus would say was the most accurate.

Students were up for the challenge and the conversations were interesting to overhear. Students argued over elements in each picture, not only identifying connections between the images and the journal entries, but giving them weight about what was most important to see in the interpretation. One image showed men in armor which was in the journal, but is also showed natives there when they shouldn't be (according to this student's interpretation). Faith was written about, but not crosses which were shown in two of the images. One image truly had natives without clothing but was missing other elements a student felt was important. Ideas were swirling, not only in heads, but also in the air.

Students were up for the challenge and the conversations were interesting to overhear. Students argued over elements in each picture, not only identifying connections between the images and the journal entries, but giving them weight about what was most important to see in the interpretation. One image showed men in armor which was in the journal, but is also showed natives there when they shouldn't be (according to this student's interpretation). Faith was written about, but not crosses which were shown in two of the images. One image truly had natives without clothing but was missing other elements a student felt was important. Ideas were swirling, not only in heads, but also in the air.

I stopped the conversation. I wanted students to make an individual decision and defend it. I asked all students to make a "claim" and "evidence" statement. I see these used more in science, but thought that this would work well here, not only because they were familiar with the format, but because it

would allow them some structure to their choice. I gave them some guidance on what they may want to write about, not only what they felt made their choice the best according to Columbus, but also what made the other options not as good. With less than ten minutes, they quickly shared their thoughts.

While I am still reading the student responses, I am seeing much of the opinion that I heard in the discussion and evidence that they took their analysis of the journal entries and were able to apply it to critique the artistic depictions.

During collaboration, two of our fifth grade teachers were studying the time period encompassing European exploration. They wanted to push their own teaching forward and had collected many resources on the typical explorers that students study. Since I have been doing several activities with primary sources, they asked if I would do an analysis of Columbus' journal entries with the students. They handed me a packet of journal entries. I agreed that we could do something with the entries.

I knew we were under time limitations, less than two hours. They were coming to the library during one of their social studies periods. If I needed more time, I could take their weekly library visit as well. That time limitation always shapes our encounters with primary sources. Here, I knew I had to put specific journal entries in front of them. I chose three that I thought revealed Columbus' intentions better than the others. In one entry from October 12, 1492, he writes about meeting natives and taking possession of the island. In another from that same day, he writes about his desire to convert the natives to his religion. In the final shared entry from October 13, 1492, Columbus writes about his search for gold.

I had three entries that highlighted intentions that would impact Columbus' and other European explorer's encounters with Americans, but I was left with a feeling of "so what?" Students could analyze these writings and come to some understandings about Columbus and possibly those that he encountered, but what would allow them to solidify their thinking in action? This is another understanding that I've come to when using primary sources with students. While analyzing using the LOC Primary Source Analysis Tool is a powerful activity, there is a piece at the bottom that reads "Further Investigation". It challenges us to take that next step with students and not to let the analysis be the end of the learning.

I had three entries that highlighted intentions that would impact Columbus' and other European explorer's encounters with Americans, but I was left with a feeling of "so what?" Students could analyze these writings and come to some understandings about Columbus and possibly those that he encountered, but what would allow them to solidify their thinking in action? This is another understanding that I've come to when using primary sources with students. While analyzing using the LOC Primary Source Analysis Tool is a powerful activity, there is a piece at the bottom that reads "Further Investigation". It challenges us to take that next step with students and not to let the analysis be the end of the learning. |

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a10998/ |

The interesting thing about the piece is that it seems to be influenced by the time period of when it was created and its creator. (I encourage you to read Rebecca Newland's ideas on sourcing and contextualizing.) Critiquing a interpretation of Columbus' landing based on his own words would provide an opportunity for students to show an understanding of the journal entries and apply that understanding to their critique.

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3g04806/ |

|

| http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/pga.01974/ |

During the students' next visit, we jumped back into the activity with them analyzing the third journal entry. After they finished this, I paired them up and gave them their final challenge. I told them I had three depictions of Columbus' first landing in the new world. They were all made after this journey and I wanted them to choose one that, based on what they knew, Columbus would say was the most accurate.

Students were up for the challenge and the conversations were interesting to overhear. Students argued over elements in each picture, not only identifying connections between the images and the journal entries, but giving them weight about what was most important to see in the interpretation. One image showed men in armor which was in the journal, but is also showed natives there when they shouldn't be (according to this student's interpretation). Faith was written about, but not crosses which were shown in two of the images. One image truly had natives without clothing but was missing other elements a student felt was important. Ideas were swirling, not only in heads, but also in the air.

Students were up for the challenge and the conversations were interesting to overhear. Students argued over elements in each picture, not only identifying connections between the images and the journal entries, but giving them weight about what was most important to see in the interpretation. One image showed men in armor which was in the journal, but is also showed natives there when they shouldn't be (according to this student's interpretation). Faith was written about, but not crosses which were shown in two of the images. One image truly had natives without clothing but was missing other elements a student felt was important. Ideas were swirling, not only in heads, but also in the air.

I stopped the conversation. I wanted students to make an individual decision and defend it. I asked all students to make a "claim" and "evidence" statement. I see these used more in science, but thought that this would work well here, not only because they were familiar with the format, but because it

would allow them some structure to their choice. I gave them some guidance on what they may want to write about, not only what they felt made their choice the best according to Columbus, but also what made the other options not as good. With less than ten minutes, they quickly shared their thoughts.

While I am still reading the student responses, I am seeing much of the opinion that I heard in the discussion and evidence that they took their analysis of the journal entries and were able to apply it to critique the artistic depictions.

Friday, October 3, 2014

Heliocentric, Geocentric, and Primary Sources

Yesterday, I had an opportunity to use one of Library of Congress' new eBooks with students. I posted some pictures on Twitter, but wanted to share a little more about the process.

I had been looking for some integration of research skills for our one fifth grade class that is currently studying space and motion. While students had mostly been studying observational aspects to space such as moon phases, their classroom teacher shared that they had been introduced to the terms 'heliocentric' and 'geocentric'.

The new Understanding the Cosmos eBook primary source set gave a great selection of primary sources that could help support that topic. Originally, I thought that I would encourage students to explore the differences within several geocentric models, but upon asking the students a few questions, it became clear that they were still hazy on what these models were and how to define them. Many students thought that it might be the solar system drawn from a different point of view, not necessarily different models of the solar system. Even though this helps explain why these models are different, they hadn't grasped the inherent differences in the models themselves. I hoped that analyzing pieces from this primary source set would help them come to an understanding of the difference.

To prepare, I first downloaded the eBook on a class set of iPads through the iBooks store. There is no charge for the eBooks. (The eBooks are currently only available on iPads, but a recent Tweet implies they are looking at other options.) This only took about 20 minutes for almost 30 iPads. I didn't have the books sync because I didn't know how the sync feature would impact a class of students using the books at once. After downloading, I found the primary sources that had heliocentric and geocentric models of the solar system. (If you're wondering, they are images 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, and 15.) Finally, I had copies of LOC's Primary Source Analysis Tool for the students.

Each student was given a primary source to analyze with no two students analyzing the same source at a table. I projected the eBook on the SmartBoard and showed students how to access the eBook, their primary source, and how to draw on the primary source, modeling some reasons they may annotate on the image. I told students we would work on defining our words, but for now, they were just to analyze their image, taking notes on the paper provided. (I did not use the included analysis scribing in the eBook because I wanted to give students a chance to have all of their writing in front of them at once and because I wanted to see their writing.)

I found that students, for the most part, had a great deal of focus on their analysis. They loved to pinch and zoom feature and used it to see details that couldn't be seen otherwise. They used the draw feature purposefully, circling things that they found interesting, unusual, or important. They used their finger to write "Why?" about some of the writings around the models. While there was sharing with others, it was purposeful. They were engaged. I did have to direct the students to write out reflections and questions on their analysis sheet. They wanted to continue to interact with the primary source and each other. While that engagement is incredible, writing out observations, reflections, and questions on the Primary Source Analysis Tool, in my opinion, helps to focus their attention and allow later conversations with each other to be elevated because they have concrete evidence of their own thinking.

After students analyzed their primary source, I asked them to confer with others at their table. There were two groups that all of these models could be grouped in, heliocentric and geocentric. I suggested they use their analysis and focus on the differences and similarities to try to help them define the words that they could not correctly define earlier.

Students talked with each other about what they noticed in their primary source. Some pointed out that the moon is drawn as a planet. Others noticed that not all of the planets were shown or that the scale was off. They explored the language and how they translated some words to figure out where a planet or the sun was in the model. What I did not expect was for them to talk as much about the language. Sol, Terra, Earthe, Sonne, Solis, Geo- and Helio- were all words that students focused on, talked about, and highlighted.

When the class shared out at the end of the session, all of the groups but one had a correct definition of 'heliocentric' and 'geocentric'. What was interesting to me was that the one group that did not have a correct definition for the terms still used a very logical explanation for their thinking. They believed that one word had to do with models that had gods or other spirits living on the planets of the solar system and the other word defined those models where the planets were barren. As they shared their focus on the images they analyzed, their thinking made great sense. That being said, by the time two groups after them had shared, they asked to change their idea based on what others had said.

This embodies why I appreciate the use of primary sources in learning. Analyzing primary sources as part of an activity encourage the struggle that leads to learning. Students had to observe, interpret, and apply their understanding of these primary sources to create a definition for a pair of words. They brought in their own understanding of the solar system and of language to help construct that understanding. They worked individually and then collaborated together to come to agreed upon meanings that weren't confirmed by the teacher until all had an opportunity to make their own learning journey. Overall, I would consider this a good first experience with using primary sources to explore this topic and a promising first use of Library of Congress' new eBooks.

I had been looking for some integration of research skills for our one fifth grade class that is currently studying space and motion. While students had mostly been studying observational aspects to space such as moon phases, their classroom teacher shared that they had been introduced to the terms 'heliocentric' and 'geocentric'.

The new Understanding the Cosmos eBook primary source set gave a great selection of primary sources that could help support that topic. Originally, I thought that I would encourage students to explore the differences within several geocentric models, but upon asking the students a few questions, it became clear that they were still hazy on what these models were and how to define them. Many students thought that it might be the solar system drawn from a different point of view, not necessarily different models of the solar system. Even though this helps explain why these models are different, they hadn't grasped the inherent differences in the models themselves. I hoped that analyzing pieces from this primary source set would help them come to an understanding of the difference.

To prepare, I first downloaded the eBook on a class set of iPads through the iBooks store. There is no charge for the eBooks. (The eBooks are currently only available on iPads, but a recent Tweet implies they are looking at other options.) This only took about 20 minutes for almost 30 iPads. I didn't have the books sync because I didn't know how the sync feature would impact a class of students using the books at once. After downloading, I found the primary sources that had heliocentric and geocentric models of the solar system. (If you're wondering, they are images 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, and 15.) Finally, I had copies of LOC's Primary Source Analysis Tool for the students.

Each student was given a primary source to analyze with no two students analyzing the same source at a table. I projected the eBook on the SmartBoard and showed students how to access the eBook, their primary source, and how to draw on the primary source, modeling some reasons they may annotate on the image. I told students we would work on defining our words, but for now, they were just to analyze their image, taking notes on the paper provided. (I did not use the included analysis scribing in the eBook because I wanted to give students a chance to have all of their writing in front of them at once and because I wanted to see their writing.)

I found that students, for the most part, had a great deal of focus on their analysis. They loved to pinch and zoom feature and used it to see details that couldn't be seen otherwise. They used the draw feature purposefully, circling things that they found interesting, unusual, or important. They used their finger to write "Why?" about some of the writings around the models. While there was sharing with others, it was purposeful. They were engaged. I did have to direct the students to write out reflections and questions on their analysis sheet. They wanted to continue to interact with the primary source and each other. While that engagement is incredible, writing out observations, reflections, and questions on the Primary Source Analysis Tool, in my opinion, helps to focus their attention and allow later conversations with each other to be elevated because they have concrete evidence of their own thinking.

After students analyzed their primary source, I asked them to confer with others at their table. There were two groups that all of these models could be grouped in, heliocentric and geocentric. I suggested they use their analysis and focus on the differences and similarities to try to help them define the words that they could not correctly define earlier.

When the class shared out at the end of the session, all of the groups but one had a correct definition of 'heliocentric' and 'geocentric'. What was interesting to me was that the one group that did not have a correct definition for the terms still used a very logical explanation for their thinking. They believed that one word had to do with models that had gods or other spirits living on the planets of the solar system and the other word defined those models where the planets were barren. As they shared their focus on the images they analyzed, their thinking made great sense. That being said, by the time two groups after them had shared, they asked to change their idea based on what others had said.

This embodies why I appreciate the use of primary sources in learning. Analyzing primary sources as part of an activity encourage the struggle that leads to learning. Students had to observe, interpret, and apply their understanding of these primary sources to create a definition for a pair of words. They brought in their own understanding of the solar system and of language to help construct that understanding. They worked individually and then collaborated together to come to agreed upon meanings that weren't confirmed by the teacher until all had an opportunity to make their own learning journey. Overall, I would consider this a good first experience with using primary sources to explore this topic and a promising first use of Library of Congress' new eBooks.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)