Years ago, when I was still in the classroom, we used translations of Christopher Columbus' journal in class. I read it to students or they read it on their own. They took on the role of a shipmate and wrote their own journal entry. It all felt "okay" but was missing something. I think a recent activity with two fifth grade classrooms got closer to meaningful learning.

During collaboration, two of our fifth grade teachers were studying the time period encompassing European exploration. They wanted to push their own teaching forward and had collected many resources on the typical explorers that students study. Since I have been doing several activities with primary sources, they asked if I would do an analysis of Columbus' journal entries with the students. They handed me a packet of journal entries. I agreed that we could do something with the entries.

I knew we were under time limitations, less than two hours. They were coming to the library during one of their social studies periods. If I needed more time, I could take their weekly library visit as well. That time limitation always shapes our encounters with primary sources. Here, I knew I had to put specific journal entries in front of them. I chose three that I thought revealed Columbus' intentions better than the others. In one entry from October 12, 1492, he writes about meeting natives and taking possession of the island. In another from that same day, he writes about his desire to convert the natives to his religion. In the final shared entry from October 13, 1492, Columbus writes about his search for gold.

I had three entries that highlighted intentions that would impact Columbus' and other European explorer's encounters with Americans, but I was left with a feeling of "so what?" Students could analyze these writings and come to some understandings about Columbus and possibly those that he encountered, but what would allow them to solidify their thinking in action? This is another understanding that I've come to when using primary sources with students. While analyzing using the

LOC Primary Source Analysis Tool is a powerful activity, there is a piece at the bottom that reads "Further Investigation". It challenges us to take that next step with students and not to let the analysis be the end of the learning.

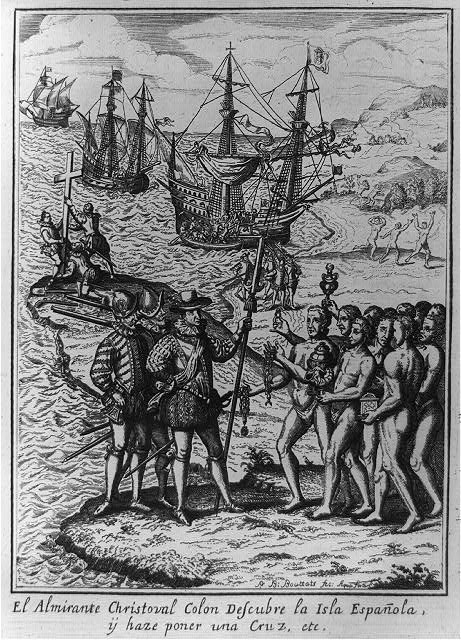

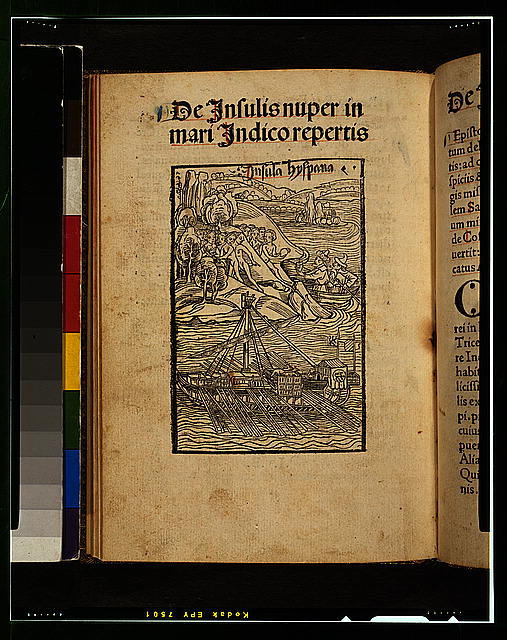

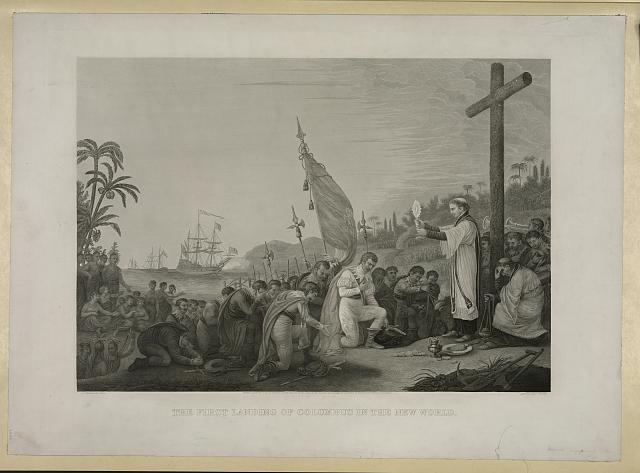

Again, I turned to primary sources. I thought about a piece of

artwork depicting Columbus' landing that was used in a

summer institute at the LOC that I attended in 2013. It was created in 1893, hundreds of years after Columbus' landing. We originally used it in a discussion where we began to form our definition of a primary source.

The interesting thing about the piece is that it seems to be influenced by the time period of when it was created and its creator. (I encourage you to read Rebecca Newland's

ideas on sourcing and contextualizing.) Critiquing a interpretation of Columbus' landing based on his own words would provide an opportunity for students to show an understanding of the journal entries and apply that understanding to their critique.

I chose three different artist renditions of Columbus' landing. I felt they had three distinct perspectives and would allow the students to focus on different perspectives of the journal entries. My resources were ready.

Students, overall, did an incredible job on the analysis of the primary sources. I like to keep my directions simple, telling students to identify anything they think is important, interesting, or unusual. There is also a warning of not thinking

everything is important, interesting, and unusual. Many reflections and questions spoke to the perspective of the natives, letting me know that they were identifying Columbus' perspective, but not solely identifying with that perspective. With some delays, we completed analyses of two of the journal entries in our first sitting. As students left, one said, "Thanks, that was fun," while I overheard another telling a fellow classmate, "I did the third analysis already even though we weren't supposed to." These were two small signs that we were on the right track.

During the students' next visit, we jumped back into the activity with them analyzing the third journal entry. After they finished this, I paired them up and gave them their final challenge. I told them I had three depictions of Columbus' first landing in the new world. They were all made after this journey and I wanted them to choose one that, based on what they knew, Columbus would say was the most accurate.

Students were up for the challenge and the conversations were interesting to overhear. Students argued over elements in each picture, not only identifying connections between the images and the journal entries, but giving them weight about what was most important to see in the interpretation. One image showed men in armor which was in the journal, but is also showed natives there when they shouldn't be (according to this student's interpretation). Faith was written about, but not crosses which were shown in two of the images. One image truly had natives without clothing but was missing other elements a student felt was important. Ideas were swirling, not only in heads, but also in the air.

I stopped the conversation. I wanted students to make an individual decision and defend it. I asked all students to make a "claim" and "evidence" statement. I see these used more in science, but thought that this would work well here, not only because they were familiar with the format, but because it

would allow them some structure to their choice. I gave them some guidance on what they may want to write about, not only what they felt made their choice the best according to Columbus, but also what made the other options not as good. With less than ten minutes, they quickly shared their thoughts.

While I am still reading the student responses, I am seeing much of the opinion that I heard in the discussion and evidence that they took their analysis of the journal entries and were able to apply it to critique the artistic depictions.